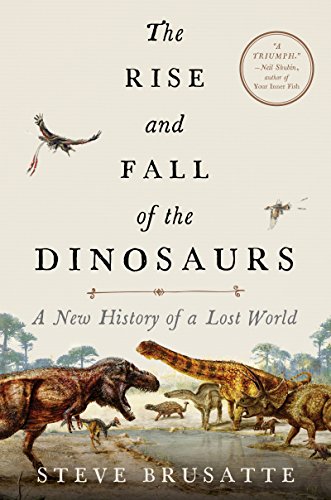

The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost World

von Steve Brusatte

Descriptions of the doom and gloom could go on for pages, but the point is, the end of the Permian was a very bad time to be alive. It was the biggest episode of mass death in the history of our planet. Somewhere around 90 percent of all species disappeared.

There have been five particularly severe mass extinctions over the past 500 million years. The one 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, which wiped out the dinosaurs, is surely the most famous.

That moment of time 252 million years ago, chronicled in the swift change from mudstone to pebbly rock in the Polish quarry, was the closest that life ever came to being completely obliterated.

Dinosaurs lived during three periods of geological history: the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous (which collectively form the Mesozoic Era).

I first visited in the summer of 2008, a twenty-four-year-old in between finishing my master’s and starting my PhD; I went to study some intriguing new reptile fossils that had been found a few years earlier in Silesia, the sliver of southwestern Poland that for years was fought over by Poles, Germans, and Czechs.

Over the course of those years, I saw Grzegorz transition from an eager, but still somewhat meek, graduate student into one of Poland’s leading paleontologists. A few years before turning thirty, he discovered, in a different corner of the Zachełmie quarry, a trackway left by one of those first fishy creatures to walk out of the water and onto land, some 390 million years ago. His discovery was published on the cover of Nature, one of the world’s leading scientific journals. He was invited to a special audience with Poland’s prime minister and gave a TED talk.

Tucking your limbs under your body, however, opens up a new world of possibilities. You can run faster, cover greater distances, track down prey with greater ease, and do it all more efficiently, wasting less energy as your columnar limbs move back and forth in an orderly fashion rather than twisting around like those of a sprawler.

Walking upright, it seems, was one of the ways in which animals recovered—and indeed, improved—after the planet was shocked by the volcanic eruptions.

Very early, they split into two major lineages, which would grapple with each other in an evolutionary arms race over the remainder of the Triassic. Remarkably, both of these lineages survive today. The first, the pseudosuchians, later gave rise to crocodiles. As shorthand, they are usually referred to as the crocodile-line archosaurs. The second, the avemetatarsalians, developed into pterosaurs (the flying reptiles often called pterodactyls), dinosaurs, and by extension the birds that, as we shall see, descended from the dinosaurs. This group is called the bird-line archosaurs.

The first true dinosaurs arose some time between 240 and 230 million years ago.

We know from lab experiments the rate at which potassium-40 changes into argon-40. Knowing this rate, we can take a rock, measure the percentages of the two isotopes, and calculate how old the rock is. Radiometric dating revolutionized the field of geology in the middle of the twentieth century; it was pioneered by a Brit named Arthur Holmes,

But there is one major caveat: radiometric dating works only on rocks that cool from a liquid melt, like basalts or granites that solidify from lava. The rocks that contain dinosaur fossils, like mudstone and sandstone, were not formed this way, but rather from wind and water currents that dumped sediment. Dating these types of rocks is much more difficult.

interesting fashion sense.

Geography class would have been easy in those days: the supercontinent we call Pangea, and the ocean we call Panthalassa.

Early in the Triassic, archosaurs split into two major clans: the avemetatarsalians, which led to dinosauromorphs and dinosaurs, and the pseudosuchians, which gave rise to crocodiles.

For the in-between cases, let’s say that Herrerasaurus and Saurosuchus share 100 characteristics but differ in the 370 others. Their distance score would be 0.79: the 370 features they differ in divided by the 470 total features in the data set. The best way to envision this is to think of those tables in a road atlas, which give distances between different cities. Chicago is 180 miles from Indianapolis. Indianapolis is 1,700 miles from Phoenix. Phoenix is 1,800 miles from Chicago. That table is a distance matrix. Here’s the neat trick about a distance matrix in an atlas. You can take that table of road distances between cities, stick it into a statistics software program, run what is called a multivariate analysis, and the program will spit out a plot. Each city will be a point on that plot, and the points will be separated by distance, in perfect proportion. In other words, the plot is a map—a geographically correct map with all of the cities in the right places and distances relative to each other.

All throughout the Triassic, the pseudosuchians were significantly more morphologically diverse than dinosaurs. They filled a larger spread of that map, meaning they had a greater range of anatomical features, which indicated that they were experimenting with more diets, more behaviors, more ways of making a living.

Far from being superior warriors slaying their competitors, dinosaurs were being overshadowed by their crocodile-line rivals during the 30 million years they coexisted in the Triassic.

villains of Watergate. It was a great accomplishment for a kid—collecting a haul of dinosaur tracks, getting his site preserved for posterity, becoming pen pals with the president. But Paul Olsen didn’t stop. He went to college to study geology and paleontology, completed a PhD at Yale, and was hired as a professor at Columbia University, across the Hudson from Riker Hill. He became one of the leading academic paleontologists in the world and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, one of the greatest honors for any American scientist.

Methane is nasty: it’s an even more powerful greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, packing an earth-warming punch over thirty-five times as great.

It’s probably not what you were expecting. After some of the largest volcanic eruptions in Earth history desecrated ecosystems, dinosaurs became more diverse, more abundant, and larger. Completely new dinosaur species were evolving and spreading into new environments, while other groups of animals went extinct. As the world was going to hell, dinosaurs were thriving, somehow taking advantage of the chaos around them.

Nothing in this inventory of growing diversity encapsulates the newfound dominance of dinosaurs quite like the sauropods. They are those unmistakable long-necked, column-limbed, potbellied, plant-devouring, small-brained behemoths. Some of the most famous dinosaurs of all are sauropods: Brontosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Diplodocus.

These were big animals, no doubt, but nowhere near the size of the creatures that left the gigantic sauropod bones. So scientists didn’t make the connection with dinosaurs. Instead, they considered the sauropod bones to belong to the one type of thing they knew could get so huge: whales. It was a few decades before that mistake was corrected. Amazingly, later discoveries would show that many sauropods got even bigger than most whales. They were the largest animals that ever walked the land, and they push the limit for what evolution can achieve. This raises a question that has fascinated paleontologists for over a century: how did sauropods become so large?

That leaves only one plausible explanation: there was something intrinsic about sauropods that allowed them to break the shackles that constrained all other land animals—mammals, reptiles, amphibians, even other dinosaurs—to much smaller sizes. The key seems to be their unique body plan, which is a mixture of features that evolved piecemeal during the Triassic and earliest Jurassic, culminating in an animal perfectly adapted for thriving at large size.

We know that sauropods had such a birdlike lung because many bones of the chest cavity have big openings, called pneumatic fenestrae, where the air sacs extended deep inside. They are exactly the same structures in modern birds, and they can only be made by air sacs. So that’s adaptation three: sauropods had ultra-efficient lungs that could take in enough oxygen to stoke their metabolism at huge size.

sauropods suddenly found themselves able to do something no other animals, before or since, have been able to do. They became biblically huge and swept around the world; they became dominant in the most magnificent way—and they would remain so for another hundred million years.

His most famous work is undoubtedly The March of Progress—that often satirized timeline of human evolution in which a knuckle-walking ape gradually morphs into a spear-carrying man. More people have probably come to understand, or misunderstand, the theory of evolution through that one image than through all of the textbooks, school lectures, and museum exhibits the world over.

In March 1877 the real fun started. A railroad worker named William Reed was returning home from a successful hunt, rifle and pronghorn antelope carcass in tow, when he noticed some huge bones protruding out of a long ridge called Como Bluff, not too far from the railroad tracks in an anonymous expanse of southeastern Wyoming.

The Allosaurus was nicknamed Big Al, and it became a celebrity dinosaur. It even had its own television special broadcast internationally by the BBC. But once the buzz died down, there remained a huge hole in the ground that was still full of all kinds of fossils that were buried underneath Big Al.

Camarasaurus is one of many enormous sauropods that have been found in the Morrison Formation. It’s joined by its famous cousins, the big three of Brontosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Diplodocus.

The sauropods weren’t competing for the same plants, but dividing the resources among themselves. The scientific term for this is niche partitioning—when coexisting species avoid competing with each other by behaving or feeding in slightly different ways. The Morrison world was highly partitioned, which is a sign of just how successful these dinosaurs were.

These northern lands—called Laurasia—were beginning to split from southern Pangea, called Gondwana, which was a stuck-together mess of Australia, Antarctica, Africa, South America, India, and Madagascar.

Other times, it’s barely noticeable, and more a matter of scientific bookkeeping, a way for geologists to break up long stretches of time without any major changes or catastrophes. The changeover between the Jurassic and Cretaceous is that type of boundary. There was no calamity like an asteroid impact or a big eruption that ended the Jurassic, no sudden die-off of plants and animals, no brave new world as the Cretaceous dawned. Rather, the clock just ticked over, and the diverse Jurassic ecosystems of giant sauropods, plate-backed dinosaurs, and small to monstrous meat-eaters continued into the Cretaceous.

all of the familiar species like Brontosaurus, Diplodocus, and Brachiosaurus went extinct, while a new subgroup called the titanosaurs began to proliferate, eventually evolving into supergiants like the middle Cretaceous Argentinosaurus, which at more than a hundred feet (thirty meters) long and fifty tons in mass was the largest animal known to have ever lived on land.

Ankylosaurs were some of the slowest, stupidest dinosaurs of all, but they made a living happily chomping ferns and other low-lying vegetation, their body armor making them impervious to attack. Not even the sharpest-toothed predator could get in a good chomp when it had to bite through several inches of solid bone.

WHEN I WAS a teenager, I watched movies and listened to music and went to baseball games—the normal stuff—but my hero wasn’t some athlete or actor. He was a paleontologist. Paul Sereno, the National Geographic Explorer in Residence, dinosaur hunter extraordinaire, leader of expeditions all over the world, and one of People magazine’s 50 Most Beautiful People, in the issue with Tom Cruise on the cover. I was a dinosaur-obsessed high schooler, and I followed Sereno’s work like a rock star’s groupie.

A few excursions led by Europeans during the colonial period had found some intriguing fossils in places like Tanzania, Egypt, and Niger, but once the colonizers left, so too did most interest in collecting dinosaurs. Not only that, but some of the most important African collections—made by the German aristocrat Ernst Stromer von Reichenbach, from the Early to mid Cretaceous rocks of Egypt—weren’t around anymore. They had the great misfortune of being kept in a museum just a few blocks from Nazi headquarters in Munich and were destroyed by an Allied bombing raid in 1944.

There was a whole group of dinosaurs like Carcharodontosaurus that lived throughout the world during the Early to middle Cretaceous. They are named, perhaps unoriginally, the carcharodontosaurs. Among the family album are three species—Giganotosaurus, Mapusaurus, and the hauntingly named Tyrannotitan—all from South America, which during the Early to middle Cretaceous was still connected to Africa.

This whole process is what we in the business call a cladistic analysis. My family tree of carcharodontosaurs helped me unravel their evolution. First, it clarified where these colossal carnivores came from and how they rose to glory. They got their start in the Late Jurassic and are very close relatives of that most terrifying predator of the Jurassic, the Butcher itself, Allosaurus.

These first tyrannosaurs weren’t very impressive. They were marginal, human-size carnivores. They continued this way for another 80 million years or so, living in the shadows of larger predators, first Allosaurus and its kin in the Jurassic, and then the fierce carcharodontosaurs in the Early to middle part of the Cretaceous. Only then, after that interminable period of evolution in anonymity, did tyrannosaurs start growing bigger, stronger, and meaner. They reached the top of the food chain and ruled the world during the final 20 million years of the Age of Dinosaurs.

Osborn was president of New York’s American Museum of Natural History and of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in 1928 he even graced the cover of Time magazine. But Osborn was no normal man of science. His blood ran blue: his father was a railroad tycoon, his uncle the corporate raider J. P. Morgan. He seemed to be a member of every wood-paneled, smoke-filled, good-old-boy backroom club there was.

published a formal scientific paper designating the new dinosaur as Tyrannosaurus rex—a beautiful combination of Greek and Latin that means “tyrant lizard king”—and put the bones on display at the American Museum, as the institution is known among scientists. The new dinosaur became a sensation, making headlines throughout the country.

Like any good celebrity, Brown was an eccentric. He hunted fossils in the dead of summer in a full-length fur coat, made extra cash spying for governments and oil companies, and had such a fondness for the ladies that rumors of his tangled web of offspring are still whispered throughout the western American plains.

They pushed and pushed the tooth until it made a half-inch-deep hole, and then used their instruments to read out how much force it required: 13,400 newtons, equivalent to about 3,000 pounds. That’s a staggering number—about the weight of an old-school pickup truck. By comparison, humans exert a maximum force of about 175 pounds with our rear teeth, and African lions bite at about 940 pounds. The only modern land animals that come close to T. rex are alligators, which also bite at around 3,000 pounds. However, we need to remember that the 3,000-pound figure for T. rex is for only a single tooth—imagine how much power a mouth full of these railroad spikes would have delivered!

Instead, she builds computer models of fossils—say, the skull of T. rex—and uses a technique called finite element analysis (FEA) to study how they would have behaved in a mechanical sense. FEA was developed by engineers and calculates the stress and strain distributions in a digital model of a structure when it is subjected to various simulated loads. In plain English, it’s a way to predict what will happen to something when some kind of force is applied to it. This is very useful for engineers.

That’s the final piece of the puzzle, the last component in the tool kit that allowed T. rex to bite so strongly that it punctured, and then pulled through, the bones of its supper. Thick peg-like teeth, huge jaw muscles, and a rigidly constructed skull: that was the winning combination. Without any of these things, T. rex would have been a normal theropod, slicing and dicing its prey with care.

There’s another scene in Jurassic Park where the freaked-out humans are told to stay still, because if they don’t move, then the T. rex can’t see them. Nonsense—because it could sense depth, a real Rex would have made an easy meal out of those sad, misinformed people.

If you cut open a bone, you can see a record of each time growth transitions from rapid to slow: a ring. That’s right—just like trees, bones have rings inside, and because that summer-to-winter switch happens once a year, that means one ring is laid down each year. By counting the rings you can tell how old a dinosaur was when it died.

This allowed Greg to compute how quickly T. rex grew each year. The number is almost too big to comprehend: during its teenage years, from about ages ten to twenty, Rex put on about 1,700 pounds (760 kilograms) per year. That’s close to 5 pounds per day! No wonder T. rex had to eat so much—all of that Edmontosaurus and Triceratops flesh fired the insane teenage growth spurt that turned a kitty-size hatchling into the King of the Dinosaurs.

There were more species than ever before, from pint-size ones to giants, eating all kinds of foods, endowed with a spectacular variety of crests, horns, spikes, feathers, claws, and teeth. Dinosaurs at the top of their game, doing as well or better than they had ever done, still in control more than 150 million years after their earliest ancestors were born on Pangea.

They happened upon the best, most complete skeleton of a teenage T. rex that had ever been found. It was the keystone fossil that told paleontologists that the King was a gangly, long-snouted, thin-toothed sprinter as a youngster, before it metamorphosed into a truck-size bone-crunching brute as an adult.

There are no other groups of animals—living or extinct—that share these things with birds or theropods: this must mean that birds came from theropods. Any other conclusion requires a whole lot of special pleading.

Wings originally evolved as display structures—as advertising billboards projecting from the arms, and in some cases, like Microraptor, the legs, and even the tail. Then these fashionably winged dinosaurs would have found themselves with big broad surfaces that by the unbreakable laws of physics could produce lift and drag and thrust.

At least in North America, where the fossil record is best, we know that T. rex, Triceratops, and the other Hell Creek dinosaurs were there when the asteroid destroyed much of the Earth. All of these facts rule out the once popular hypothesis that dinosaurs wasted away gradually due to long-term changes in sea level and temperature or that the Indian volcanoes had started to pick away at the dinosaurs earlier in the Late Cretaceous, a few million years before the end.

Instead, we found that there is no doubt about it: the dinosaur extinction was abrupt, in geological terms. This means that it happened over the course of a few thousand years at most. Dinosaurs were prospering, and then they simply disappear from the rocks, simultaneously all over the world, wherever latest Cretaceous rocks are known.

There are some things, however, that do seem to distinguish the victims from the survivors. The mammals that lived on were generally smaller than the ones that perished, and they had more omnivorous diets. It seems that being able to scurry around, hide in burrows, and eat a whole variety of different foods was advantageous during the madness of the postimpact world.

I’m here to find fossils.

As you recall, mammals got their start alongside the dinosaurs, born into the violent unpredictability of Pangea over 200 million years ago in the Triassic. But mammals and dinosaurs then went their separate ways.