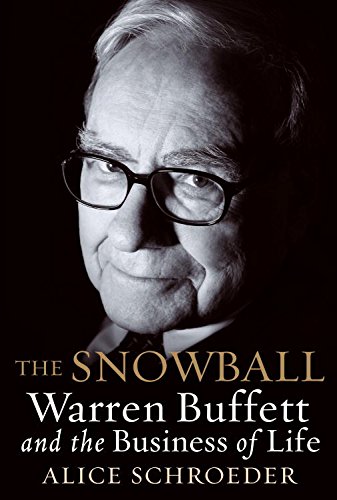

The Snowball: Warren Buffett and the Business of Life

von Alice Schroeder

“In the short run, the market is a voting machine. In the long run, it’s a weighing machine.

“Now, Aesop was not much of a finance major, because he said something like, ‘A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.’ But he doesn’t say when.” Interest rates—the cost of borrowing—Buffett explained, are the price of “when.” They are to finance as gravity is to physics. As interest rates vary, the value of all financial assets—houses, stocks, bonds—changes, as if the price of birds had fluctuated. “And that’s why sometimes a bird in the hand is better than two birds in the bush and sometimes two in the bush are better than one in the hand.”

So autos had an enormous impact on America, but in the opposite direction on investors.”

“As of a couple of years ago, there had been zero money made from the aggregate of all stock investments in the airline industry in history.

Ultimately, the value of the stock market could only reflect the output of the economy.

“Praise by name, criticize by category” was Buffett’s rule.

Whereas Munger wanted only respect, and didn’t care who thought he was a son of a bitch.

They wore the same sort of gray suits draped stiffly over their frames, the inflexible bodies of men who have spent decades reading books and newspapers rather than playing sports or working outdoors.

the four months Howard had gone without making a sale when he first started his business.

He counted how often letters recurred in the newspaper and in the Bible. He loved to read and spent many hours with books he checked out of the Benson Library.

Warren’s fondness for minutiae continued to develop. His parents and their friends—who called him “Warreny”—got a kick out of his party trick of naming state capitals. By fifth grade he had immersed himself in the 1939 World Almanac, which quickly became his favorite book. He memorized the population of every city. He got a contest going with Stu over who could name the most world cities with populations over a million.11

“It could make me independent. Then I could do what I wanted to do with my life. And the biggest thing I wanted to do was work for myself. I didn’t want other people directing me. The idea of doing what I wanted to do every day was important to me.”

“But,” the book cautioned, “you cannot possibly succeed until you start. The way to begin making money is to begin.… Hundreds of thousands of people in this country who would like to make a lot of money are not making it because they are waiting for this, that, or the other to happen.” Begin it! the book admonished, and explained how. Crammed with practical business advice and ideas for making money, One Thousand Ways to Make $1,000 started with “the story of money” and was written in a straightforward, friendly style, like someone sitting on the front stoop talking to a friend.

This concept—compounding—struck him as critically important. The book said he could make a thousand dollars. If he started with a thousand dollars and grew it ten percent a year: In five years, $1,000 became more than $1,600. In ten years, it became almost $2,600. In twenty-five years, it became more than $10,800.

Compounding married the present to the future. If a dollar today was going to be worth ten some years from now, then in his mind the two were the same.

Sitting on the stoop at his friend Stu Erickson’s, Warren announced that he would be a millionaire by the time he reached age thirty-five.

One lesson was not to overly fixate on what he had paid for a stock. The second was not to rush unthinkingly to grab a small profit. He learned these two lessons by brooding over the $492 he would have made had he been more patient. It had taken five years of work, since he was six years old, to save the $120 to buy this stock. Based on how much he currently made from selling golf balls or peddling popcorn and peanuts at the ballpark, he realized that it could take years to earn back the profit he had “lost.”

Know what the deal is in advance.

Since a young age Warren had studied the lives of men like Jay Cooke, Daniel Drew, Jim Fisk, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie. Some of these books he read and reread.

Everybody wants attention and admiration. Nobody wants to be criticized. The sweetest sound in the English language is the sound of a person’s own name. The only way to get the best of an argument is to avoid it. If you are wrong, admit it quickly and emphatically. Ask questions instead of giving direct orders. Give the other person a fine reputation to live up to. Call attention to people’s mistakes indirectly. Let the other person save face.

Now he had a system. He had a set of rules. But it did you no good to read about the rules. You had to live them. I am talking about a new way of life, said Carnegie. Warren began to practice. He started at a very elementary level. Some of it came naturally to him, but he found that this system could not be applied in an automatic and easy manner.

Unlike most people who read Carnegie’s book and thought, gee, that makes sense, then set the book aside and forgot about it, Warren worked at this project with unusual concentration; he kept coming back to these ideas and using them.

No one else in high school was a businessman. Just from pitching newspapers a couple of hours a day, he was earning $175 a month, more money than his teachers.

Warren kept his money in a chifforobe at home, which no one but he was allowed to touch. “I was in his house one day,” says Lou Battistone, “and he opened up a drawer and said, ‘This is what I’ve been saving.’ And he had seven hundred dollars in small bills. That’s a big stack, let me tell you.”12

Warren had discovered the miracle of capital: money that works for its owner, as if it had a job of its own.

Within a day or two, Warren played like a demon. The first thing every morning, he got up, went straight over to the Student Union, found a hapless victim, and slaughtered him at the Ping-Pong table. Before long, he was playing Ping-Pong three or four hours at a stretch every afternoon. “I was his first victim at Penn,” Chuck recalls. Ping-Pong kept Warren out of the suite and away from the record player while Chuck was studying.

A stock is the right to own a little piece of a business. A stock is worth a certain fraction of what you would be willing to pay for the whole business.

Use a margin of safety. Investing is built on estimates and uncertainty. A wide margin of safety ensures that the effects of good decisions are not wiped out by errors. The way to advance, above all, is by not retreating.

Mr. Market is your servant, not your master. Graham postulated a moody character called Mr. Market, who offers to buy and sell stocks every day, often at prices that don’t make sense. Mr. Market’s moods should not influence your view of price. However, from time to time he does offer the chance to buy low and sell high.

Bill Ruane, a stockbroker at Kidder, Peabody, had found his way to Graham through his alma mater, Harvard Business School, after reading two important and memorable books—Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? and Security Analysis.

“I learned that it pays to hang around with people better than you are, because you will float upward a little bit. And if you hang around with people that behave worse than you, pretty soon you’ll start sliding down the pole. It just works that way.”

To make this decision to defy the advice of his two great authorities—his father and Ben Graham—was an enormous step for Warren. It required him to consider the possibility that his judgment might be superior to theirs. Yet he was certain he was right. He might have walked out a window if his father told him to—but not if it meant leaving a Moody’s Manual full of cheap stocks behind.

In that first month, he had parked himself in the file room at Graham-Newman and begun to read through every single piece of paper in every single drawer in an entire room filled with big wooden files.

“We would look up stuff and read. We would go through Standard & Poor’s or a Moody’s Manual and look at companies selling below working capital. There were a lot then,” recalls Schloss.

These companies were what Graham called “cigar butts”: cheap and unloved stocks that had been cast aside like the sticky, mashed stub of a stogie one might find on the sidewalk. Graham specialized in spotting these unappetizing remnants that everyone else overlooked. He coaxed them alight and sucked out one last free puff.